It is easy to work up a smile while writing about Andrew Lanyon. To anyone vaguely familiar with his work, he invokes predecessors that invite the offhand and maybe patronising classification of ‘artist-eccentric’. One thinks of Lewis Carroll with his madcap humour, verbal ingenuity, interest in photography and the absurd; Heath Robinson with his stupendously complicated mechanical monsters; Glen Baxter with his poker-faced hilarity and, more austerely and significantly, Lanyon’s father, Peter Lanyon, who single-handedly re-defined landscape painting in Cornwall, dynamically evolving a vocabulary of abstraction.

But what tradition does he follow? Let us say the tradition of the educated polymath who can write and draw and shows an interest in kinetics and scientific exploration. As tradition often accompanies inheritance, it would be relevant to note the important archival resource Andrew has been entrusted with, relating to Lionel Miskin, Sydney Graham and Man Ray.

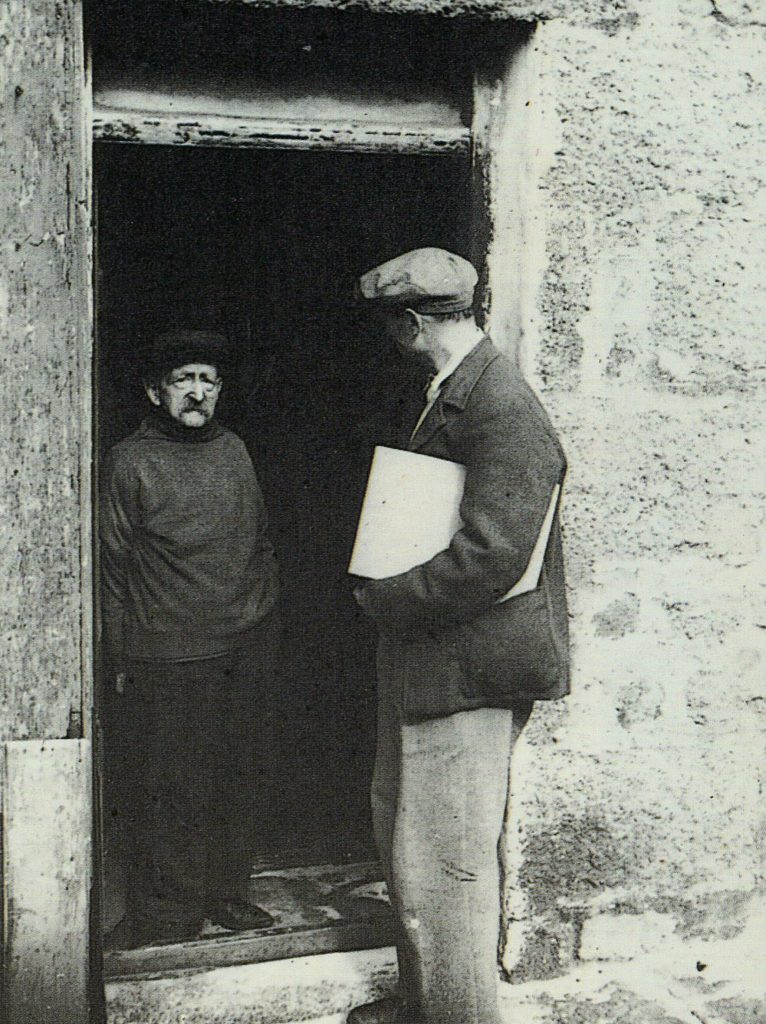

He was born in 1947 and from 1966 to 1968 studied at the London School of Film Technique, co-organised the Durham Surrealist Festival for which he produced a catalogue. After that, he worked as a freelance photographer as well as assistant editor to Ambit, a literary quarterly associated with J. G. Ballard and avant-garde artists and writers. This combination of the visual and literary is evident in many of his paintings which ‘snap’ into meaning by way of a caption or title.

A clue to his outlook is his membership of the London Institute of Pataphysics, a society that honours the legacy of Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), a Parisian intellectual with an ebullient personality who single-handedly re-defined dramatic technique by presenting on stage the comic monster, Ubu, who was ruthlessly devoid of any likeable characteristic. Pioneer absurdist, storyteller and playwright, Jarry devised the law that applied to exceptions and made the nihilistic observation: “We won’t have destroyed anything unless we destroy the ruins too.” Rebelling against society and bourgeois convention, he drank, wrote skits, art essays, stories and poems and devised spectacular, self-demeaning antics to draw attention to himself. His posthumously published Exploits and Opinions of Dr Faustroll, Pataphysician (Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll, pataphysicien) has as its hero an ‘antiphilosopher’ who was born at the age of 63 and explores Paris in a sieve. Dr Faustroll holds to the tenets of pataphysics that strive to “explain the universe supplementary to this one”. It is not easy to speak confidently of pataphysics, but it is a great leveller, finding everything equally nonsensical and inviting everyone to make up their own nonology. Certainly Jarry, whose last words were a request for a toothpick, had the courage of his anti-convictions.

Devising alternative realities was a preoccupation of both Alfred Jarry and many who followed him. Lanyon is not obviously attracted to the solemn predictive mechanics of science fiction, but pays lip-service to fantasy, taking forward the fairy legacy of Richard Dadd and Cornish folklore, save his fairies belong to the mind-worlds of Gulliver’s Travels and Samuel Butler’s Erewhon, for they antithetically relate to our civilisation and its foibles. Aside from the successful and popular illustrated work A Fairy Find (that charmed the gay community of New York), there was Lanyon’s exhibition of wands used by ‘fairies’ to effect different modes of enchantment. That took place at the Pataphysical Museum in Highgate and attracted a good deal of interest.

Alfred Jarry’s brand of raging humour and gleeful destructionism does a good job in the sense of releasing the human prisoner from the shackles of scientific, artistic and moral dogma. It explodes pedantry and evangelism alike, but there are those who do not warm to it. I remember attending a play by Eugene Ionesco with a critic who told me later that he did not enjoy it. When I asked him why, he said, “There’s no hope there.” I grasped what he meant. If everything is absurd, if all values are powdered down into a tasteless paste, if all notions deserve equal derision, what about faith, hope, love and charity, all those high ideals that priests and worthy folk used to uphold? What about human dignity? What about the concept of redemption? All of that is sacrificed and what is left is the maniacal cackle of Ubu Roi.

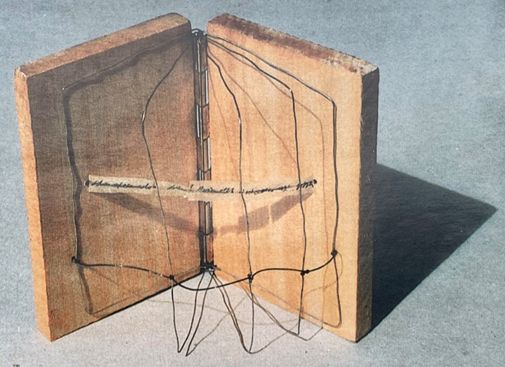

Not that this applies to Lanyon personally who, like David Hume, may think such things but never acts them out save in his imagination. As an artist, he maintains high standards, helping many others along the road to recognition as well as overseeing his own productions. The majority of his titles emerge by way of his single-handed publishing operation involving hand-bound works with pasted illustrations, often using quality paper and cut-out board and card covers, all incredibly satisfying to handle and done with exemplary care and skill. Additionally, to be taken into account is his ‘Gormenghast’ or ‘Tristram Shandy’ sequence of ‘pataphysical’ novels or ‘ficciones’ featuring the Rowleys of Rowley Hall, a metaphysically boundless, post-modern, Victorian-style, stately manor madhouse in which everything and nothing happens, one anti-event cancelling another, a verbal flea circus of vertiginous possibility, promiscuously mingling profundities, inanities and ingenuities.

However, looking deeper, this genial literary monument is vitalised by scalpel slashes that haemorrhage onto the page.

“Time was once continuous. But when a thing was made of interval, Time was slotted into a clamp like ham and cut thin, chopped into ever finer slices with cameras and clocks.

Time, a dying bull, bled darkness from the lances in its neck and as it pawed the ground the bloody darkness spread.”

This tragic scene is uncannily illustrated by a candleholder seeping an elongated shadow of black, waxy blood that emulates the stems and heads of flowers – a blossoming estocada. So what we have, in fact, is a perfect imagist poem served by an illustration that is fitting as well as subtly shocking.

The drama of the foregoing highlights Lanyon’s work as a film-maker, drawing upon everything from jokes and songs to rustic cavorting and ingenious, miniaturised narratives of catastrophe, utilising wood, wire, flame, water and tiny figures, There are also savage hand-drawn cartoons that possess an authentic shock-value with their threatening, occasionally malevolent imagery. Presented with this massive oeuvre, it would take a confident critic to deliver anything more than a tentative, partial assessment.

WAR OF WORDS

Of his present book and exhibition Von Ribbentrop in St Ives – dealing with the antics of Hitler’s foreign minister in Cornwall – let us initially establish that he has visited the subject of warfare previously but often in purely abstract terms, demonstrating a strong satiric agenda in his transposition of hostilities to purely abstract constructions, notably in his illustrated fiction A Persistence of Visions:

“A battle between words and images takes place in a medieval setting. Writing sends silent e’s as spies to eavesdrop on its foes. Conspiring with speech, it sends regiments of invective to batter images in their castles with metal trebuchets, typewriters. Rotten sentences hurled like dead cows land in pastoral scenes.”

Similarly the disguise or camouflage theme, prominent in Ribbentrop, features in A Novel Solution in which Mervyn Rowley “travels abroad and disguises himself as foreign scenery so he can send postcards of himself not anywhere all over the world.” This is pushing humour to its limits, undermining both foreign travel and personal identity that for some has become a raison d’être of existence. It is funny and mildly de-stabilising, too. Given the complications of existence implied by the realm of subatomic matter alone, many prefer their literary entertainments to supply a model of the world with at least a vestigial foundation or element of dependability. Everyone wants to discover an anchorage, a secure compass-point, whether in a home or another person, and those creators who deny them this stability have not only the capacity to generate delight but also a concomitant sense of vertigo and panic, like clambering up a pyramid of marbles that slither down at the slightest pressure.

THE CRACK IN THE IMAGINATION

Lanyon opens Ribbentrop dramatically. As in a surrealist film, he exposes to the eye a vertical crack of darkness dividing the slightly open doors of a cupboard, akin to a crack in the mind through which a black stream of apprehension flows, amplified by a surge of adrenaline that bears a chill of terror.

This galvanising image is followed not by revelation of the cupboard’s content or Dr Caligari stepping forth, but by further speculation on the imagination when, in a brilliant if perplexing linkage, Lanyon likens the brain to a glove puppet controlled by a hand whose five fingers stand for the five senses. Normally, of course, an idea is portrayed as being seeded or growing in the mind rather than grasped by a hand. When the hand is displaced to the brain, there is a natural tendency to extend the metaphor, asking who is operating this glove puppet? Is it God or the Artist playing God?

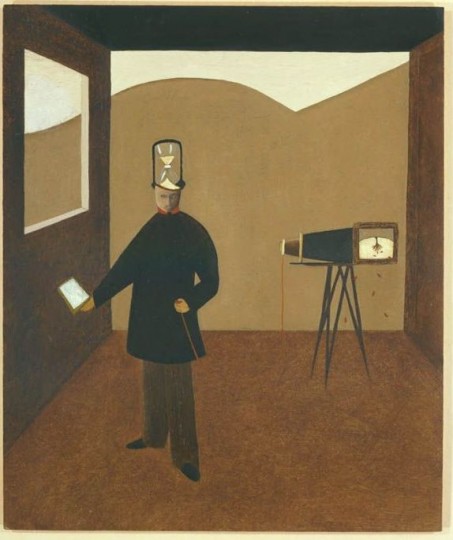

This exemplifies Lanyon’s fit and active mind working at its peak, ideas and counter-ideas throwing out tendrils and connections that, as it turns out, involve the devouring nature of the imagination, the special demands of war upon the painting community in St Ives, camouflage as a means of de-familiarising one’s locale, Von Ribbentrop as strutting mock-Cornishman, preparing the way for invasion, Ben Nicholson’s exploration of the mystery of Alfred Wallis (how to create a style out of sheer indifference to such matters), abstraction as a military strategy, edible art, the deployment of language to ‘naturalise’ atrocity and the tentative suggestion that the latter may be curtailed by an imagination that is ever re-making itself, thus rendering it incapable of fixing into the brutalising logic of the death camps.

Playfully Lanyon argues that the authorities favoured abstraction during wartime as literal art might keep the enemy informed. In the same vein, he has fun with Alfred Wallis, depicting a U-boat commander guiding himself around the Manacles using the painter’s rendering as a map. Similarly with Von Ribbentrop’s collecting of postcards to assist the Nazi takeover and his instatement as emperor of the duchy. Mix this in with the love interest of Ribbentrop’s affair with Mrs Wallis Simpson, plus his aide Spitzy’s romantic skirmish with a daughter of the Bolithos, and the narrative starts to skip and release a few balloons – indeed, it becomes quite a party. Some of it is whimsical, verging on the fey, but other parts arise from a deeply engaged interior dialogue, notably on how the self-taught naïf, Alfred Wallis, provided oblique instruction to Ben Nicholson, resulting in the sophisticate unlearning himself so that he should paint less self-consciously and produce something even more intellectually authoritative.

Hence Von Ribbentrop proves an informative, provocative work, forcing through startling connections. Plenty of white space frames the statements, so that they breathe freely and stand alone. Ingenious and several-angled, it eschews a flowing thematic unity, preferring a mosaic or spreadsheet approach wherein words and images resound and work upon each other like slogans in an echo chamber. Hence it is a bit like the verbal equivalent of the Coney Island Big Dipper. You find yourself conceptually shaken, shattered and stirred. Take this for instance:

“It is by keeping our imaginations active by moving our minds between pairs of extremes, of long-shot and close-up, or of space and time, or of temperature, that we allow an imaginary pendulum to sway from side to side, describing a circle as it reaches the different pairs of opposites, like quiet and cacophony, hope and despair.”

A sentence later these fluctuations quieten into rigor mortis, out of which arises the question: “Might language be partly to blame for leading us into the kind of uniform thinking that allows well-meaning people to be led into a shoeshop and fitted for jackboots.” What have we here? The notion of syntax trapping a voice in an attitude epitomised by the request, “A pair of jackboots, please.” Any object may trigger a desire for possession, especially if there has arisen a commonality of need through a political situation. This assertion throws out yet another bud, specifically “would anyone have listened to Hitler if he’d worn tights”.

Though the Führer did relax in lederhosen occasionally, it is customarily the mournful obligation of artists to flaunt fancy dress and funny hats, outraging and tilting at conventional notions, while ruthless demagogues push ahead with their holocausts and shootings. Nevertheless, Lanyon’s hopping from allusion to leading question and puncturing levity pre-empts the possibility of the reader falling into a stupor.

THE TORTURED VASE

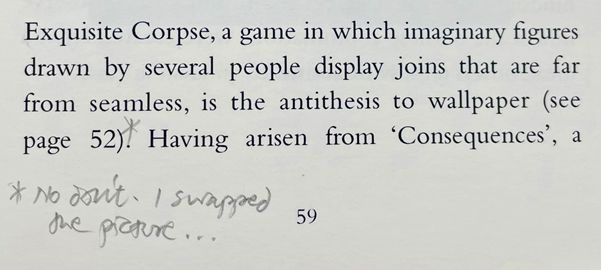

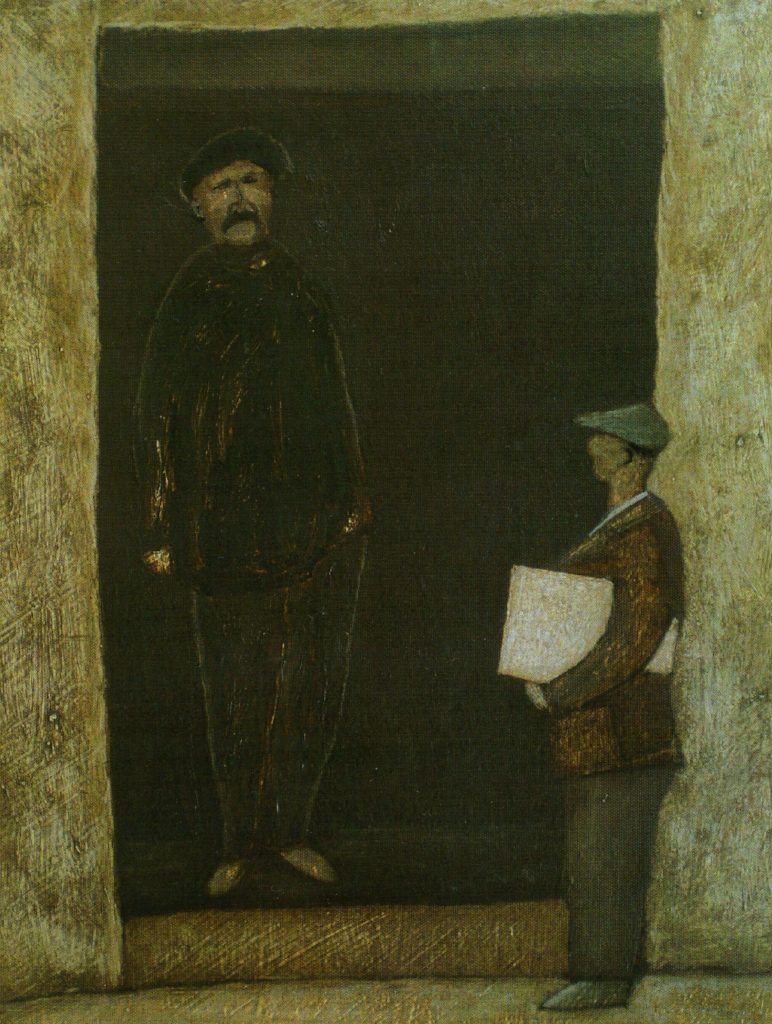

Swashbuckling polemics aside, there is symmetry in Ribbentrop. What began as an opening door ends on a closing one, the final image being the train door shutting on the diplomatic sortie of Von Ribbentrop as he leaves St Ives, knowing by now war is inevitable. The illustrations serving this tale of love, art, war, camouflage, espionage, sabotage and philosophy are even more eloquent than the prose. By turns they are alarming, nostalgic, tragic and wittily pertinent, mixing sepia shots of Hitler, pictures from a German airman’s album, urban and seashore scenes, provocative and haunting original artworks whose childlike placidity of technique belies the ferocious irony implied, such as a woman shooting flowers – killing the thing she most loves, thus tempering her spirit for the conflict to come. Similarly themed is a fetching study of botanical sadism entitled ‘A Vase of Flowers Undergoing Torture’, but without the caption a spectator would barely take in that the flowers’ stems are writhing because of the electrodes wired to their heads. Equally jolting is a woman on Porthminster Beach eating an ice cream from which drip white stains that convey implications of both carnality and bloodshed. Also on show is a pair of wooden galoshes used by German soldiers to wade through the snow of the Eastern Front. Their protruding tongues are personified as in argument, one urging the other to put the best foot forward and the other arguing for retreat.

This is fanciful but why not? Any attempt at an accurate record has to be concerned with causation or how one thing leads to another, especially a wartime narrative that implies a flurry of adjustments and special precautions. The joins that connect events are always suspect, the linear flow of words not finding an equivalent in the complex, radial vibrations issuing from a single happening. It is, if you like, impossible to pinpoint how a state of affairs led to a particular outcome or consequence: thus historical prose narratives, even if supported by primary sources, are plausible surface illusions, works of art rather than chronological exactitudes.

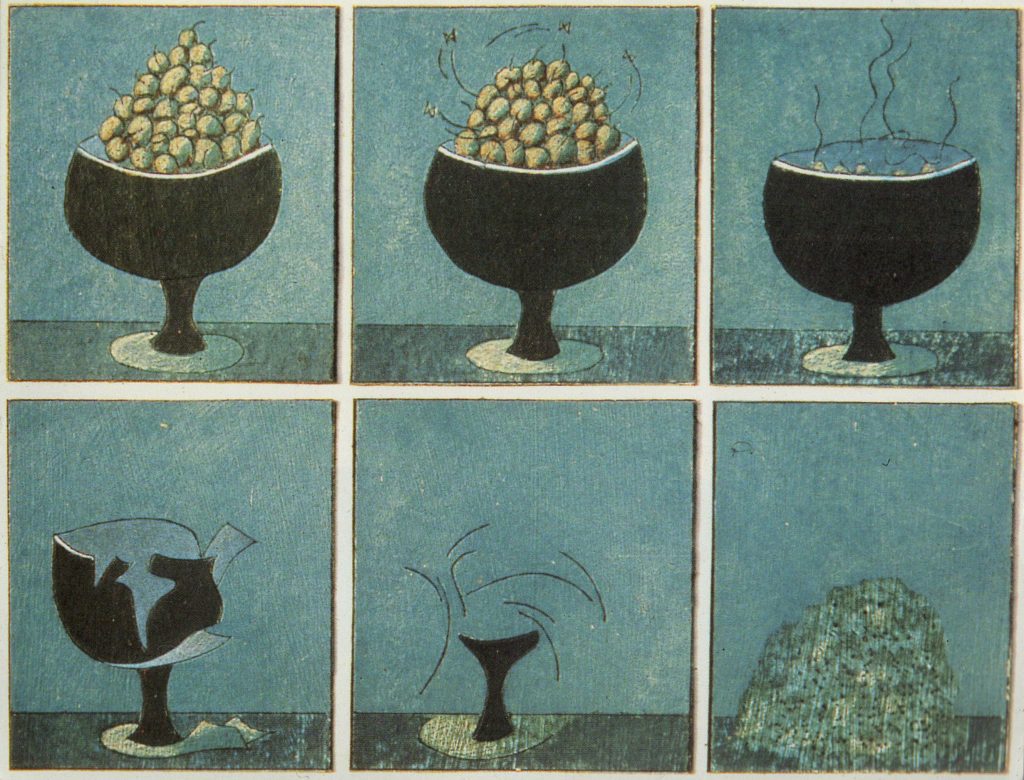

Such yawning enigmas leave Lanyon free to play the causal clown, tracing strategies and attitudes taken up by both the artistic and civilian communities of St Ives, who are obliged to educate themselves in the necessary deceit or functional lie. But he does not routinely conscript conventional assumptions. Instead he fitfully chooses to radically adjust his viewpoint, being much taken with the notion of ‘resistentialism’ – how objects appraise or initiate resistance against the human world. Hence he privileges us to share the viewpoint of a vase whose destiny it is to be mutilated by a succession of different artistic styles and also that of a cliff about to be photographed by a U-boat.

“As soon as Nicholson broke with the tie to likeness, he was free to turn his attention to the relationships between simplified forms. But from the point of view of all the objects themselves, the disfigurements to which they were subjected were no less upsetting than the experiences of cliffs faced with German cameras pointed at them from U-boats. For these cameras snapped at those coves and inlets like serpents, to take them back to their young.”

The violence of metaphor is arresting, the beak of a camera ‘snapping’, the disfigurement wrought by paint on canvas and the image of hunger applied to strategists eager for information. Objects are endowed with the greed and desires of their operators, corrupted by human motive, animated by acquisitiveness. In a specialised sense, in relation to the clashing swords of human intentions, war may be viewed as a perpetual, incurable state of affairs.

Throughout his alert enquiry, Lanyon finds time to salute the common round, the daily task, though what it entails may be devastating.

“Divesting war of all moral considerations, we might imagine how pilots who bombed St Ives felt when flying over the sea on a lovely day, how the rush of adrenaline and sense of purpose was hardly any different from what any painter or poet feels, and when the day was over, though some had broken a gasworks and killed a woman, and others had finished off a sonnet, or a sea view, all felt a sense of achievement at work well done.”

Reading such a passage makes us grateful that language is bloodless. In a perilous way – for some feel uneasy about such analogies – it is able to smooth over the dreadful fates to which some of us are assigned, for apparently, during aerial raids on St Ives in 1942, Porthmeor and Porthminster beaches were “peppered and the cinema roof looked like a colander” while “the audience emerged frightened, their faith in unreality shaken.”

If they were watching a war film, things might have been truly bewildering. positing claims between conflicting realities or unrealities. We are reminded of Günter Grass’ play The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising, in which the ostensibly revolutionary playwright, Bertolt Brecht, directs his version of Coriolanus in 1953 while, outside on the street, the real bloody battle, between East German workers and the government, is taking place.

STARRY NIGHTS AND FIRE BOMBS

Countering the larks are grimmer passages that relate to atrocity and mass execution. Lanyon is simultaneously aware of war as grim sacrifice and also as a state of affairs that ushers in wondrous visual dynamics. If we place side by side Van Gogh’s ‘Starry Night’ and a sky crackling with firebombs, similar celestial statements or metaphors assail the eye. Both are shows of light, and yet, in moral terms, the first is associated with mystical exaltation and the second with death and destruction. Yet both possess the same type of enticing surface appeal. This is why Oscar Wilde proclaimed “all art is immoral” in that it tends to arouse aesthetic pleasure in inappropriate contexts. Thomas de Quincey provocatively suggested that it was possible to refer to a “beautiful murder” by judging the effectiveness and grace of execution in relation to clumsier felonies. Since then the doctrine of “art for art’s sake” has been leading us into grosser and grosser territory, including the Nazi death camps.

From the point of view of a film producer, two immense battling armies make up the ultimate participative production on a scale more grand than anything devised by Cecil B. deMille. War is conceptual theatre at its most dramatic and earnest, and the actors have literally got to be prepared to play their parts to the death. Not only does it put on an awesome display but effortlessly generates a wreckage of sculptural statements, creating its own enthralling, modernist ‘Waste Land’, amazing constructions of twisted metal, cross-sliced buildings, massive powder-puffs of cordite and the ultimate nuclear mushrooms that may one day put an end to history. This line of argument may come over as conceited and offensive, but violence-inspired artists did write hymns to the ‘Cubist slug’, the tank, and other hardware of destruction – notably Marinetti and the Futurists. In a perversely anarchic way, they welcomed war as a cleanser of the spirit, a detonator of decadence and instigator of change. The slate is wiped clean for a scribe to record whatever new narrative happens to appear.

ART AND THE PHENOMENAL WORLD

Beyond the shadow of war, another argument of cosmic proportion infiltrates Lanyon’s prose, and that concerns art’s relation to what philosophers tentatively class as the phenomenal world. From the beginning, literal or figurative painters have depicted what they see in terms of the separation of objects, animals and plants, highlighting configurations and intensities, achieving unitary harmony through use of tone, line and colour, With the advent of Cubism, Surrealism and Abstraction, the stable identities of the perceived world became subverted and undermined. Picasso’s saddle and handlebar standing for a bull’s head portrayed how artists were sitting astride the horns of the dilemma. How much of the visually decoded world were they prepared to recover and discard? They desired the clarity of distinct forms, so that they could twist, shatter and mutilate them, hopefully salvaging a minimal semblance to spark off the suggestion of an intention. But with pure abstraction and conceptual art, the final severance was achieved and there was little point in seeking new extremes. What was conceptual art anyway? If one constructed an immense wooden frame at the base of the Matterhorn, so that the whole mountain appeared to be enclosed within, would that be the ultimate landscape statement or the ultimate gesture of creative bankruptcy?

The problem has tended to make the historically alert artist – who analyses rather than just turn out – revert to satire and the absurd. And Lanyon may be seen as both celebrating and railing against the almost eerie desert of freedom in which his imagination runs riot – simultaneously delighting in and being appalled by the narcissism and self-absorption of his vocation. He mocks its value but can only demonstrate his opposition by producing more. He brings out Anti-Art books, shoots Anti-Art films and brandishes works of art that supposedly guy the discipline they embody yet at the same time vindicate it by their skill and charm. Not only is he effortlessly original, he is also staggeringly literate and by that I do not mean fluent. He can forge sentences that have a graceful, acid-etched quality and stand as definitive or near-definitive statements:

“In desperate times this quicksilver of the imagination is far more potent than the body’s adrenaline, because it can move as fast as light or set suddenly into anything. In its role as master of ceremonies, the imagination performs metamorphoses, quick-change acts and impersonations for all the amazing music hall turns in our heads. And the imagination can flow like a river into moulds carved by circumstance, or by turning acid it can etch images as powerful as any cave painting on our inner walls. However, we cannot even, by sensitising ourselves through viewing art or by making it ourselves, ever hope to penetrate the armour put in place to protect the magma of rage.”

The provocative end statement brings about a shift – an irony for which the reader is unprepared. The phrasing is idiosyncratic, “The armour put in place to protect the magma of rage”, suggesting man’s relationship with his violent instincts has a protective, paternal aspect, a somewhat morbid suggestions that Freud might or might not have hailed.

In spite of precision of language and technique, along with a reflexive tendency to draw disquieting comparisons and outré parallels, one gets the impression that Lanyon – like the Austrian novelist Robert Musil – regards events as largely interchangeable, and that what is ultimately important to him is the aura of ghostliness that haunts our gestures, lies and consequences – that “Does this furore of human effort amount to anything at all?” self-questioning that culminates in an individual’s effacement and, by proxy, that little segment of the cosmos that resides inside his skull. The very freedom of speculation he exercises, his view from ‘everywhen’, implies a doubt about the ultimate relevance of mortal striving. But there is so much laughter, delight and variety in his exploration that we feel privileged to attend his exhibitions and take our place as fellow travellers across the ocean of artists’ palettes that besiege the shores of his St Ives or along the road that winds through the dense thickets of a mind in which all sorts of conceptual con-men and hallucinatory highwaymen wait in ambush.